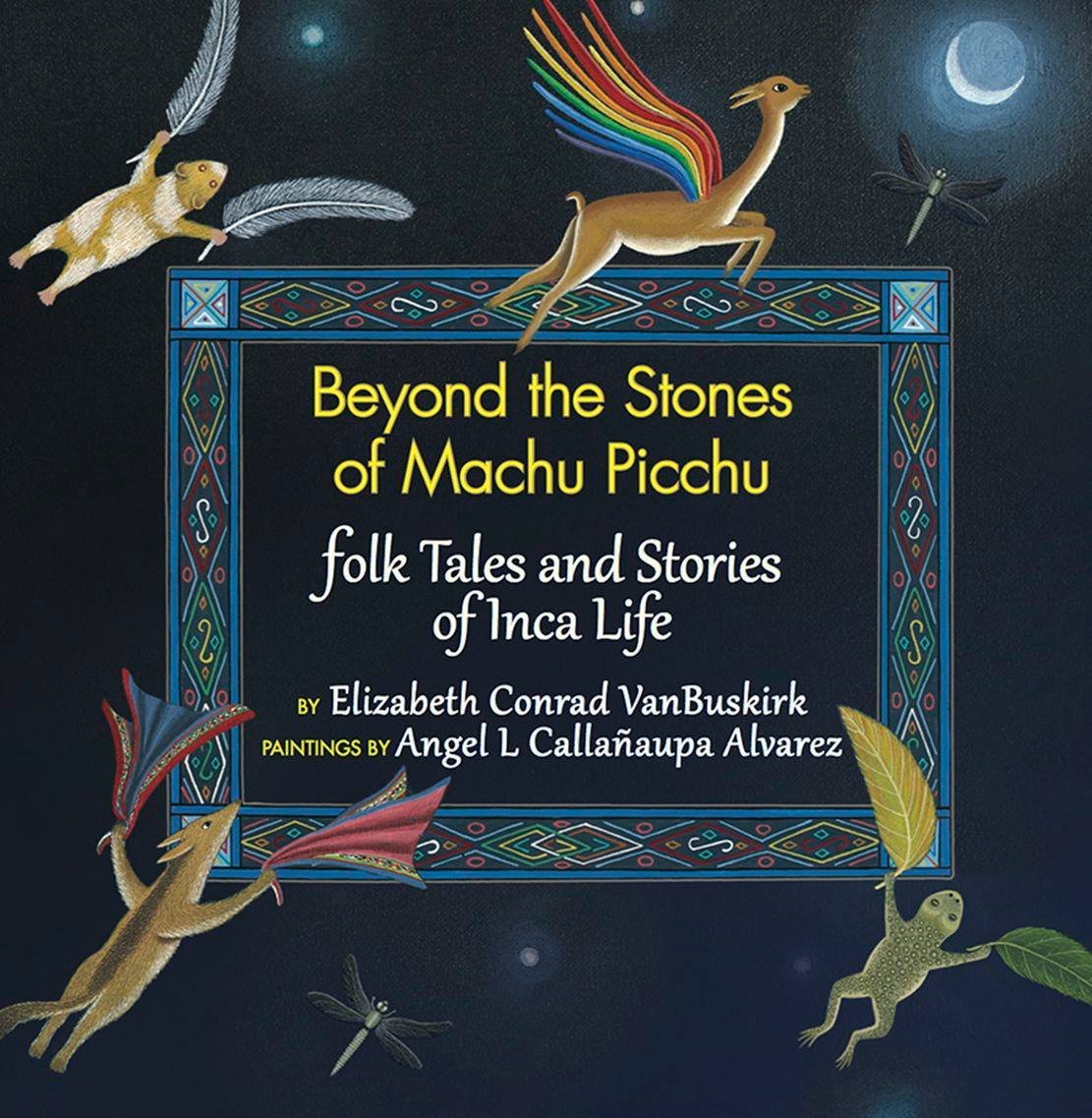

Beyond the Stones of Machu Picchu

Folk Tales and Stories of Inca Life

Along with writing, my strong other interest has long been the study and love of Andean textiles. After courses in art and archaeology at Radcliffe Institute, I found a region of the world, the high Andes of South America, where weavings were created as the primary art. In college I had never seen such innovative art created with fibers. Peru and Bolivia have hosted a series of kingdoms that flourished for over two thousand years. Andean weavers experimented with every textile technique ever known in the world. Art, especially fiber art, held ritual meaning—based on a reverence of nature. How vital this focus seemed to me. I fell in love with the beauties I saw in museums and books and began to relate the works to their religions and cultures.

What of those traditions today? Are many Inca people still alive? Does weaving still serve as religious ritual? It was hard to find this kind of information. I needed to explore more. I would have to travel to Peru. As a writer, there was much I wanted to put together.

With my husband, David, I visited the old Inca capital of Cusco, Peru and outlying high-altitude villages. Fortunately, we came to know Nilda Callañaupa, an already-renowned 24-year-old weaver who grew up in the village of Chinchero. I encountered weavings everywhere, some reminiscent of past masterpieces. Nilda shared a great deal about the still-existing Inca culture. We became entranced. We could not say goodbye. We would return. And we did, many times, a total of eight visits. As we became close to Nilda’s extended family, I began to write stories about Inca children and families and took notes for a book.

“The book” was to become two books. Beyond the Stones of Machu Picchu, short stories for young readers was published in 2013 by Thrums Books, Colorado, an offshoot of Interweave, a press focusing on textiles and fine book design. Through fiction I hoped to give young Norteamericanos a sense of the life and culture of Inca people today. The second book, Patterns in the Andes, a travel memoir is in process.

When I met Nilda’s brother, Ángel, it was a delight to see him making paintings on wood, some depicting scenes of Andean life and rituals that I was yet to observe. What an opportunity! I asked him to illustrate my stories. Thus started the happy coordination of Beyond the Stones of Machu Picchu. To describe the book, I excerpt below sections from an article by Armando Zarazú. Though the stories are fiction, each based on a personal conflict, he describes the rituals and settings. The article was published in Connecticut’s Hispanic newspaper, Identidad Latina (translated from Spanish by David Weinstock).

“Among the customs of Andean life…the first hair cut is an important event in a child’s life, a source of joy and conviviality of interlocking family ties. In the story ‘The First Haircutting,’ the author presents a complete view of the meaning of family relationships and the deeper meaning of what “compadre” and “comadre” means to the Andean inhabitants… In “Shepherds in the Mountains,” a tender story of a young shepherd and his flock of sheep, we learn about “the man-land,” the landscape viewed as having human qualities, with respect and veneration of the Pacha Mama, Mother Earth…

Ms. VanBuskirk’s story ”The Ice Mountain,” is based on the holiday known as Quyllur Riti, whose origins date back to the pre-Hispanic period, celebrating the importance the cycles of the moon had for the ancient Incas. With the arrival of Catholicism, the Inca festival was mixed, through the new, religious syncretism, to become a colorful annual pilgrimage in the snow to the mountain Qullqipunku in Sinakara Valley near Cusco…

Reading this book, written in English….. will bring you a closer and better understanding of the Andean culture. It is also adorned with excellent paintings by the Chinchero-born artist, Ángel Callañaupa Álvarez, made especially for this book. His art is inspired by traditions, legends, superstitions, and particularly an Andean vision of the cosmos. What’s more, for better understanding, the book has a glossary with the meaning of the Quechua words that the author uses in her stories”.

El Centro de Textiles Tradicionales del Cusco, The Center for Traditional Textiles of Cusco

As we traveled in highland Peru, David and I both found ourselves animated by the creativity, fortitude, and humor of Inca people we met. But we had arrived at a critical time. Indigenous Inca people live in the most glorious but perilous mountain surroundings—relying on farming almost vertical slopes and raising animals. Despite the complex weavings, many live in poverty. I was surprised to find that families often used textiles as currency, as did the great past emperors who gifted great textiles to lords, expecting the other to reciprocate in some way. In modern times this practice has meant selling off treasured family pieces to merchants and outsiders. It seemed that each indigenous household still enjoyed at least one weaver, but the tradition was fast dying out. If nothing could stop the downfall, the 3,000-year-old textile tradition would be lost in a generation. Nilda tried to convey her great concerns to us. What could be done?

David and I ended up helping Nilda establish El Centro de Textiles Tradicionales del Cusco, The Center for Traditional Textiles of Cusco, at first under the auspices of Cultural Survival. Thanks to Nilda’s leadership, the Center grew rapidly and continues, Nilda even leading a revival of the most glorious of ancient Peruvian textile techniques. The Center, now a well-visited Museum in Cusco, houses a museum shop and busy center where village weavers can come to gather, demonstrate and give workshops. Of most importance, the Center works actively with eleven traditional villages including children’s weaving groups in each village. As many say, Nilda has worked wonders.

We traveled to Peru and Bolivia eight times, visiting villages with Nida. At home, in Boston, then Vermont, how did David and I fit in? For the first years we served as a northern support system for the new Center. While Nilda did her remarkable work in Peru, I collaborated with Maria Tocco, Director of Cultural Survival—first choosing a U.S. board with David and me acting as co-chairs. David supplied fine photographs. There was a lot of writing to be done. With the help of my son, Eric, I established the Incas.org educational website, Ancestors of the Incas, wrote the first newsletters, visited schools, worked with Vermont teachers and assembled an Inca traveling kit for schools. Nilda visited us in Boston, then Vermont. She gave talks and workshops in the U.S. and Canada.

The Center reached out to everyone interested in Peru and the burgeoning project. I served as Guest Curator of an exhibition at the University of Vermont Fleming Museum of Art, Weaving the Patterns of the Land displaying Andean textiles, photographs by David VanBuskirk and descriptive texts. I later co-taught courses about teaching Inca history and culture at the University of Vermont’s College of Education and Social Services.

After ten years David and I resigned as chairpersons of the U. S board. The new board has been outstanding and the expanded project under Nilda’s direction thrives today. My passion continues, to spread the word about the richness of Andean life and culture. Now I have turned back to my beloved writing, my book of poetry, Living with Time, finished, almost ready to send out.